What do you mean by “only intact slave dwelling” left in the City of Austin?

The two-story Slave Quarters building at the Neill-Cochran House Museum is the only slave dwelling that is recognizable as such in the original city of Austin townsite. What we mean by that is that this is the only building that you can see and understand as a place where enslaved people once lived and that is accessible to the general public. A one-room slave dwelling located in downtown Austin was expanded into a single-family home; this private residence is not accessible and is no longer recognizable as an antebellum building, much less one that enslaved persons would have inhabited.

One of the benefits of this project is that individuals are reaching out to our research team to alert us to other physical reminders of enslavement in the city. We are aware of a building that was likely a dwelling for enslaved persons on an early Austin farmstead. The former Wallace-Burleson-Moore farmstead is described in a 2014 cultural resources survey. It is, however, located on City of Austin land within the airport and is inaccessible to the public. Another building that was not built as a slave dwelling but may have been used as one by the second owner—merchant George Hancock—currently stands in Rosedale in a commercial context. That building is described on page 29 of the 1995 issue of the Rosedale Ramble.

The reality is that in this city where one-third of the population was enslaved in 1860, enslavement is embedded in some way, shape, or form in every surviving building from the period. What makes the NCHM Slave Quarters particularly significant is that it still stands in its original context and is available to the public.

What is next for the Reckoning with the Past project?

The Museum and leadership team are beta testing guided tours of the Slave Quarters - keep an eye on the upcoming events section of our website for tour opportunities.

The museum also is working with noted muralist artist Fidencio Duran to produce three murals for the main house that will provide visitors with a glimpse of what it would have looked like out the back windows of the house before the 1900 addition was completed. Visitors to the house would have looked out on the yard as they dined and would have been served by an enslaved person before emancipation or a free laborer after 1865 who would then have returned outside, walking out of a door from the dining room directly into the yard. We hope to install this new work by the end of 2024.

How has the Slave Quarters building changed over time?

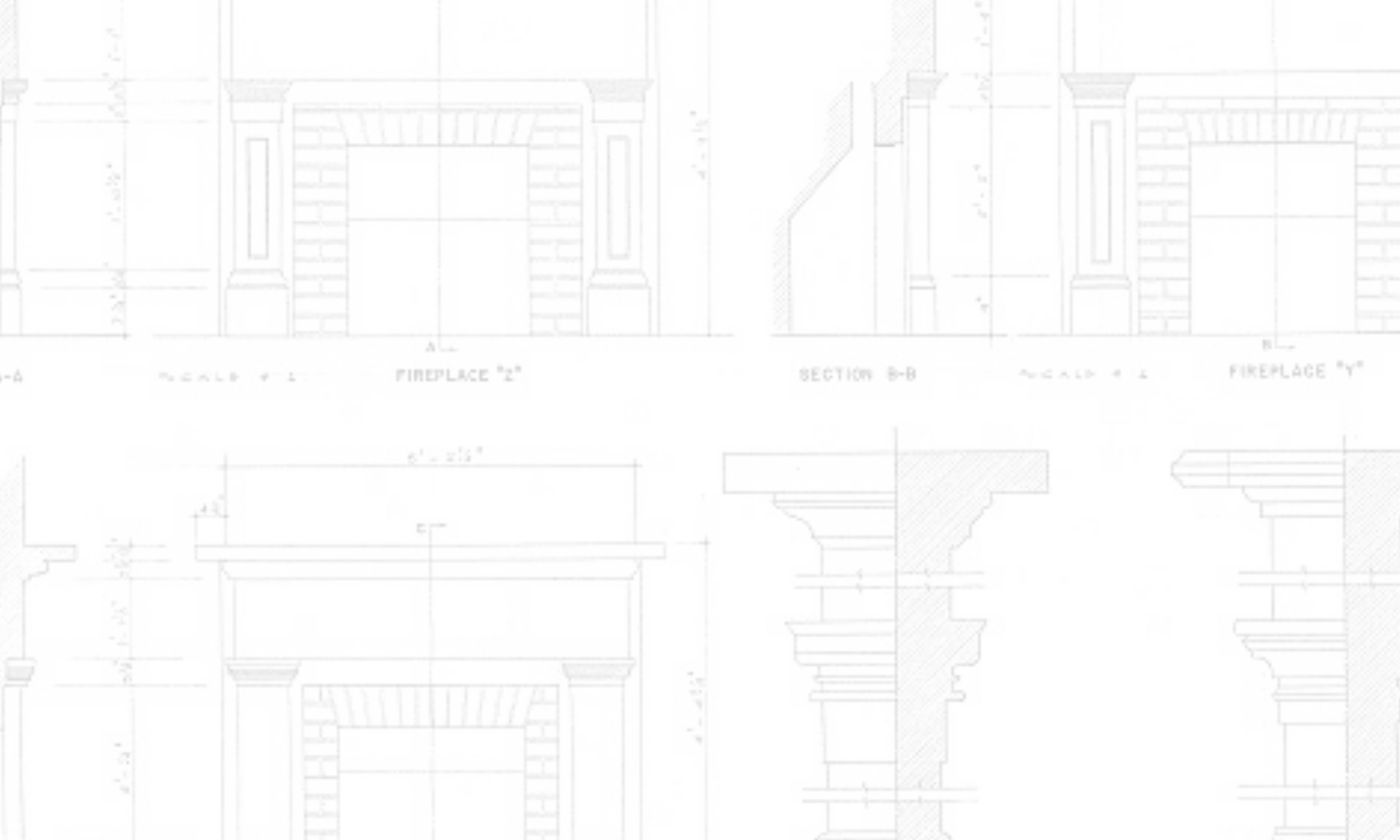

The building has always been two stories, with two window openings upstairs and one downstairs. It is not entirely clear whether the windows were glass from the beginning, however. The first floor originally was dirt, and sits about 10 inches below the current floor level. We have exposed that original floor level around the edges of the set kettle. There was no ceiling to the first or second floor – in both cases, the “ceilings” revealed the beams above. Originally interior access between the two floors was through an opening accessed by a ladder.

The set kettle on the first floor is a real mystery. It may have been original, but it is unusual for a chimney to be built on the inside of a structure if it is original. Further, the brick does not look like the kind of brick Abner Cook used during the 1850s. However, it could have been remnant brick from another project. Certainly, the set kettle dates to the 19th century and would have been appropriate for heating large quantities of water required by contemporary domestic work – by the 20th century stoves had come into use.

The exterior staircase has moved over time. We believe that the original exterior staircase was on the south façade, as you see it today, because of the ladder opening on the east side. For a period of time in the 20th century, the stair was on the east side. It was moved back to its current location during a 1970s restoration project.

Are you working with descendant communities?

We have not been able to connect with descendants of any of the enslaved or free people of color specifically associated with our site history, though we continue to hope that new research will open doors to identifying descendants. We are however talking with descendants of enslaved and free Black Austinites and their family histories and their input on this project are critical to its success.

I’d love to learn more about this aspect of Austin history. Are there resources you recommend?

This is an element of Austin history that is only now gaining focused attention. We have produced a short volume titled Reckoning with the Past: Slavery, Segregation, and Gentrification in Austin (2021) that is available through our online gift shop.

And Grace Will Lead Me Home: African American Freedmen Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865–1928 (2009) by Michelle Mears is an excellent overview of the freedom colonies of Austin.

As We Saw It: The Story of the Integration of The University of Texas at Austin (2018) by Gregory A. Vincent and Virginia A. Cumberbatch et al. looks at the experience of the first Black University of Texas at Austin students.

Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (2018) by Andrew Torget provides an excellent overview of the important role the cotton economy played in the establishment of Texas as a nation and then as a US state.

Purchase the Book!

To learn more about the Slave Quarters, the experience of life at this site, and the broader narrative of the way race has played a role in Austin history, you can purchase a copy of our book, Reckoning with the Past: Slavery, Segregation, and Gentrification in Austin from our online gift shop. The media coverage of A Weekend for Community and for the project more broadly is on the Press & Media page of our website.