The Power of Place: Thoughts on Gullah Country

In early March, I accompanied the Friends of the Neill-Cochran House Museum to Savannah, GA and to Beaufort and Gullah Country, South Carolina on our annual member trip. These trips dive deep into a region’s history and culture to help us ground ourselves in the diversities as well as the commonalities in the American experience.

The day we spent in Beaufort and then in Gullah Country was extremely powerful. We worked with local guides who did an excellent job. Beaufort, SC was Pat Conroy’s hometown, and also the filming location for the Big Chill and some portions of Forrest Gump, among many other movies. The sleepy town, with an incredibly intact historic district that goes on for blocks and blocks and blocks, owes a lot both to Conroy and to the film industry, and I have found myself thinking back to Beaufort over the past two months as we have been under quarantine. Economies that depend on tourism or on a sector like the film industry are going to struggle for the foreseeable future.

The real highlight of the day was when we left Beaufort and headed east towards Gullah Country. The Gullah live in the Low Country of South Carolina and Georgia and are descended from enslaved people who came to the United States from Africa. They were able to maintain elements of their linguistic heritage and the creole language spoken today is known as Gullah. We visited the sea islands to the east of Beaufort, areas that in the pre-Civil War period were home to sprawling plantations and the thousands of enslaved people who worked there.

Two sites resonated deeply with our group that afternoon. First, we visited Penn Center, a school founded by two abolitionist women from Boston in 1862. While I have traveled all over the United States, and I know my Civil War history, nonetheless as someone who is from Texas and now shares Texas history through our antebellum site, I found it disorienting to be standing on a site in what I think of as the deep, deep South, at a school for freed slaves established as the war raged across the country. Because, of course, Texas enslaved people were not freed until the end of the war, specifically after the reading of “Military Order #3,” from the balcony of the Ashton Villa (the historic house museum resonance runs deep!) in Galveston on June 19, 1865.

And here we were, tucked away on a sea island, which felt remote from everything. Penn Center, which I will admit I had never encountered in a history book, remained an important site for its history and for its contemporary activism through the Civil Rights era. As we walked the site, we came to a corner of the property with a small white bungalow, surrounded by azaleas and camellias and framed by draping spanish moss. The home was built for Martin Luther King, Jr., a frequent visitor to Penn Center, and he wrote the first draft of his “I Have a Dream” speech here. Suddenly, for me, this quiet, out of the way country school site reached out to touch a much wider cultural and historical American current. The school closed in the 1980s, but a visitor’s center remains open and the site is now a part of the National Park System’s Reconstruction Era Monument.

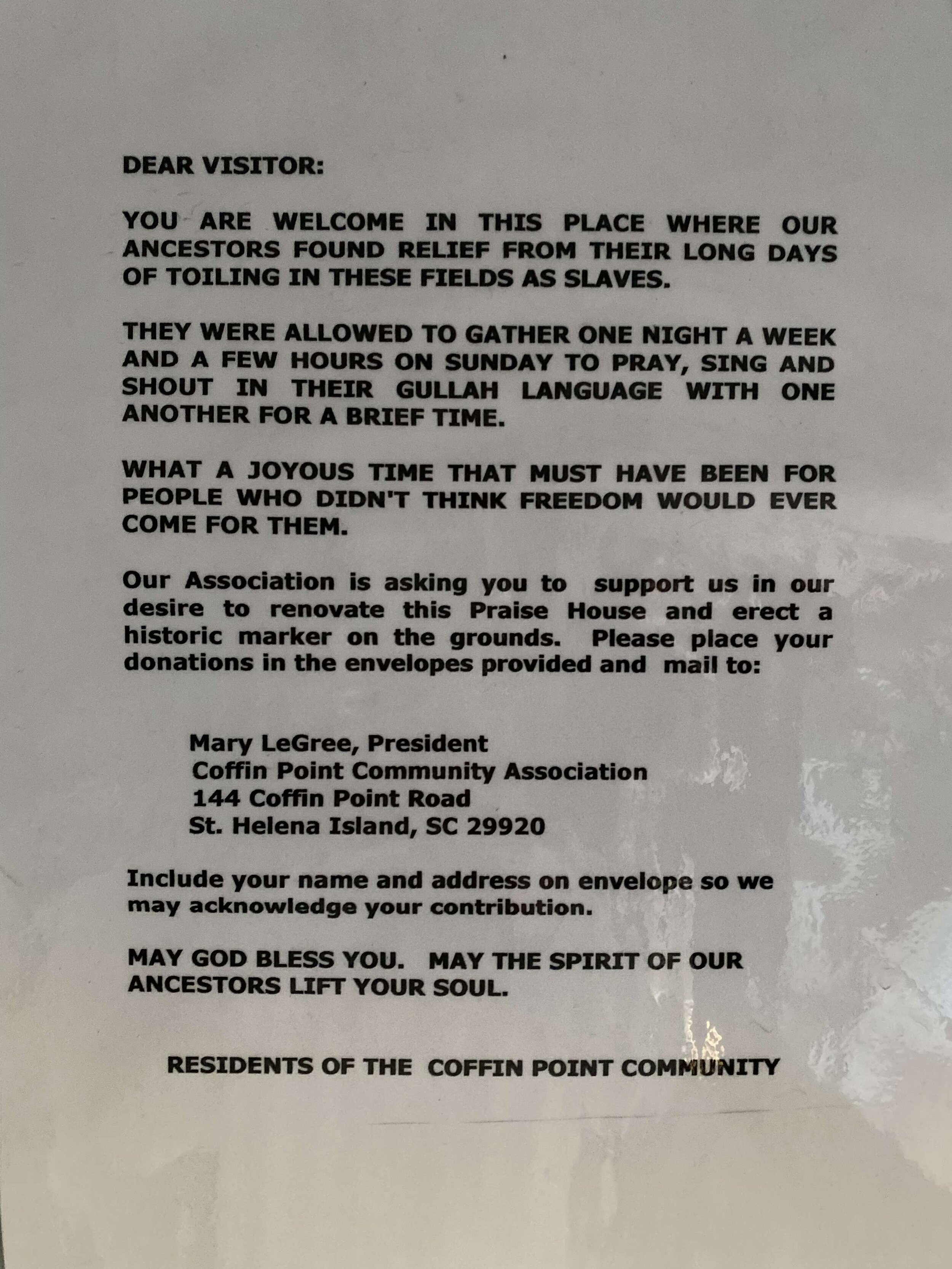

Our final stop was at a Praise House on the grounds of the former Coffin Point Plantation. I was familiar with Chapels of Ease, those places planters built for communal worship when they did not wish to travel back to town for Sunday services. In contrast, I had never seen and certainly never had entered a Praise House, a structures built by enslaved people with salvaged materials and their enslavers’ permission to use for communal gatherings and as houses of worship. Through our guide, we were able to go inside, sit, and listen to a recording of the 23rd Psalm, read in Gullah. The space was intimate - our group of 20 made it through the door, but it was hard to close behind us because of the tight quarters, and our heads came close to brushing against the ceiling. This small structure was a resource for 300 enslaved people, located miles from their housing on the plantation, and where they worshipped separately - men on Tuesdays and women on Thursdays.

In the early days of historic preservation in the United States, preservationists focused almost exclusively on the grand, and on places associated with the grand (wealthy, famous, sometimes infamous). Today, more preservationists are recognizing the importance that all types of historic spaces can have on our understanding of the past. We will never get to a “complete” understanding, but all of us who visited Penn Center and the Coffin Point Praise House felt the connection between past and present in those places, and we walked away feeling that we had a deeper understanding of how the past continues to live on in the present.

— Rowena Houghton Dasch